Maridelle Levya

"So though my mom had told me, don't let your skin get any darker, that was the first time that I realized everyone thinks brown skin looks like dirt. I just remember feeling like I was ugly and I would always be ugly."

01. Immigrant

02. Darker

03. Dirt

04. White House

05. Rejection

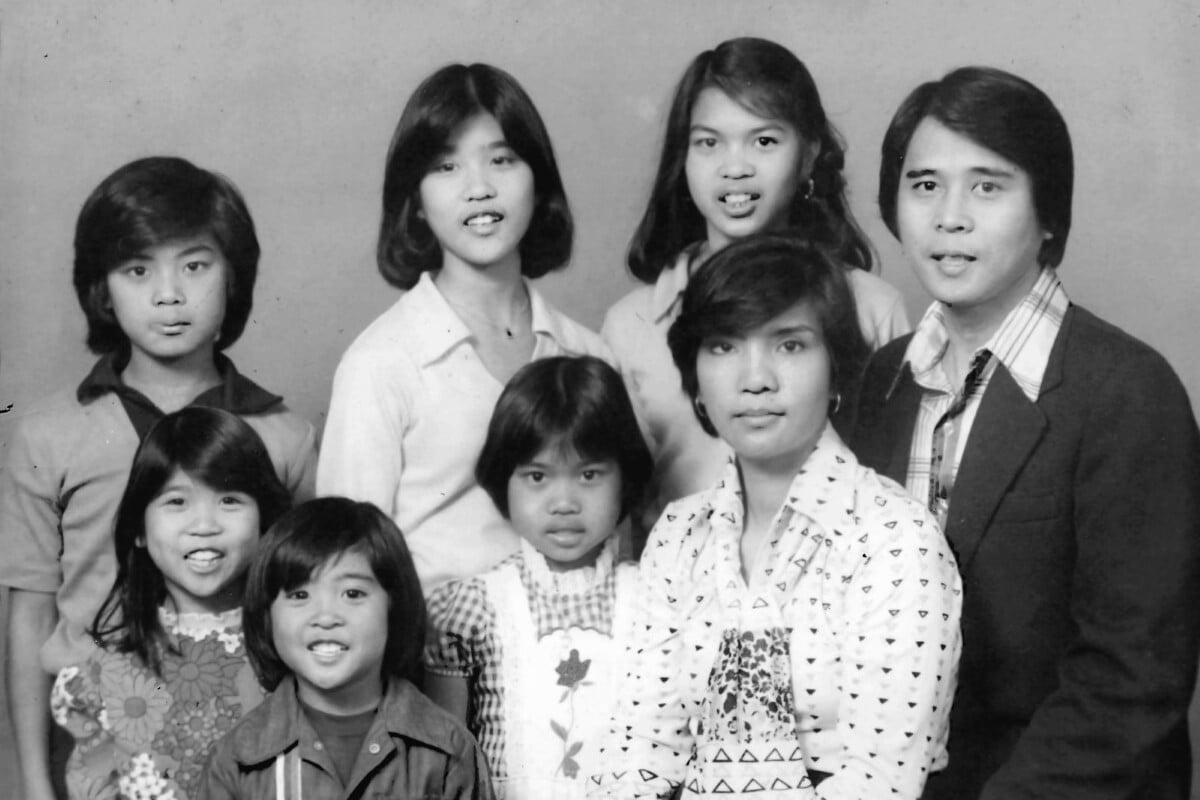

I was born in Manila, Philippines. I was 3 years old when my family immigrated. I come from a family of six children. We had the three that had lighter skin and the three that had darker skin. The three who had darker skin were my two brothers and myself and really, with our culture, darker skin is considered not as good as lighter skin. My mom would say that it’s not that bad for boys to have darker skin, which means it’s bad for girls. That’s something that I always knew for a long time. I thought it was just my family that believed that, or Filipinos.

When I was 8 years old, my family moved from South Seattle, which was a really diverse neighborhood, to the Eastside to Kirkland. The new school I went to, I was the only non-white child. It was in the middle of the school year so it was really hard―definitely felt like I didn’t belong, didn’t fit in. One of the things that this new school had that my old school didn’t was specialist day and we had art one day. It was the first time I got to paint with paint brushes on an easel and I was super excited. I did my whole thing, had a great time, and was just a total mess after and had gotten paint all over my hands. And I remember turning to the boy next to me and saying something like “I’ll have to go wash my hands, they’re all dirty,” and he said to me, “Your skin always looks like dirt, it doesn’t matter if you wash your hands.” So though my mom had told me, “don’t let your skin get any darker,” that was the first time that I realized everyone thinks brown skin looks like dirt. I just remember feeling like I was ugly and I would always be ugly. And it really doesn’t matter when people tell you you’re pretty if when you’re 8 years old, you’ve accepted that you’re ugly. I’ve tried to tell myself that it’s not true, and sometimes believe that’s not true but I go back to that.

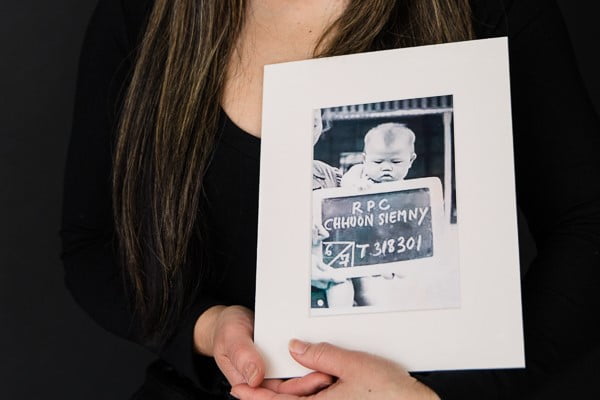

I got to be really aware of noticing all of the differences, all the things that weren’t ideal. I didn’t want to be who I was. I’ve only dated White guys so I knew I would marry someone White and I wanted to make sure my children had lighter skin than me. Growing up I thought, “I’m not going to take my husband’s last name,” but I definitely did and one of the reasons is that he has a very American last name. Even after getting divorced, I kept that last name. I liked my identity, at least my name didn’t sound Asian or Filipinio. What it has meant for me to change my last name back to my birth surname really has meant this kind of autonomy, an independence and starting that journey of accepting who I am, who I was when I was born, my heritage, where I came from. And the irony is, if you think about autonomy and where I came from, being Filipino means that you have a heritage of colonization and not being autonomous and free. I have a Spanish based last name now. What was a Filipino last name 500 going on 600 years ago? I don’t even know.