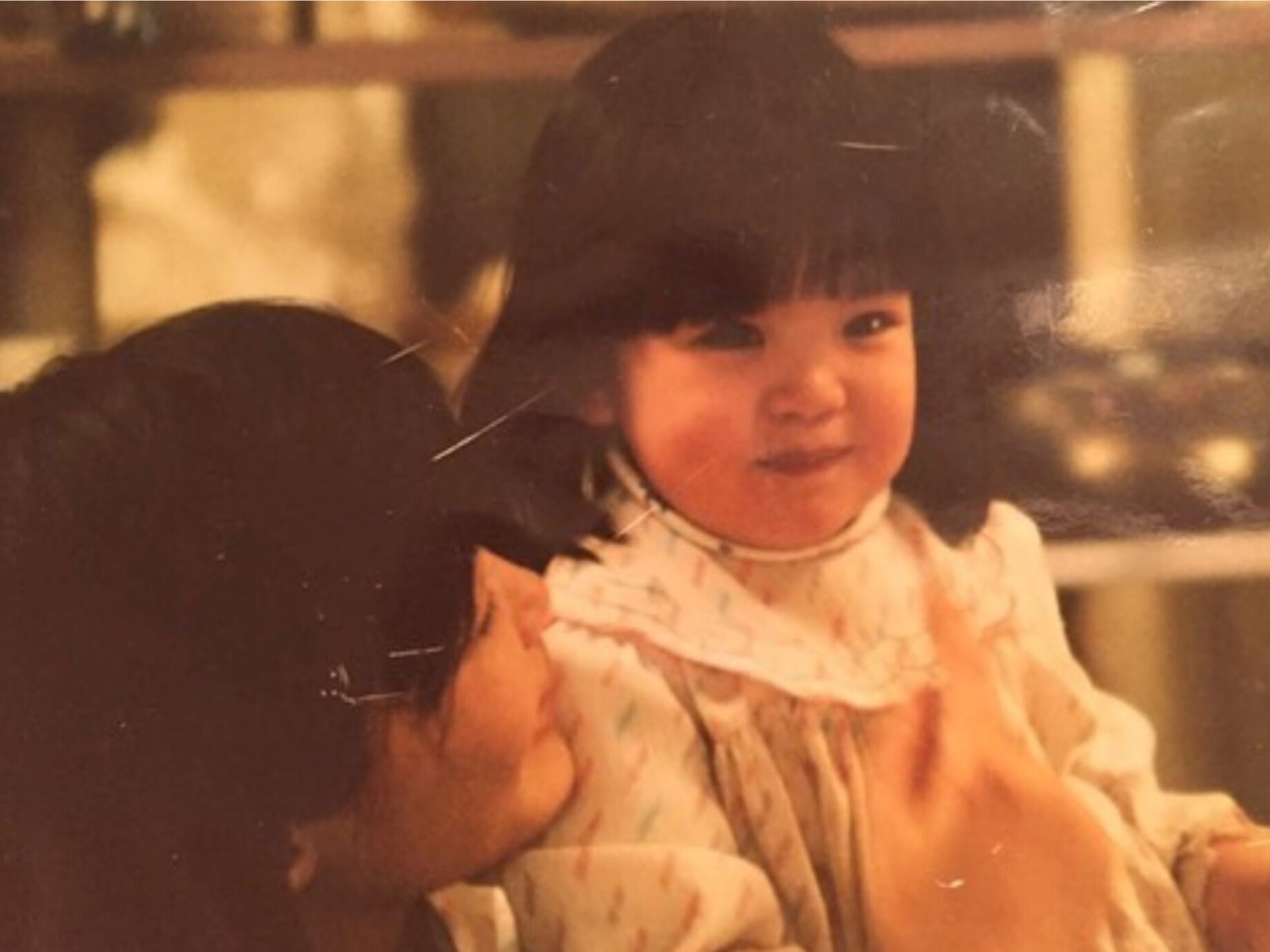

Dany Srey-Snow

Dany Srey-Snow

My name is Victoria Dany Srey. Victoria felt like my “white” name. It was my American name which my mom found from the soap opera, The Young and the Restless. Only recently, have I been able to reclaim my identity through my middle name, Dany. It’s my Khmer name, which only my family members would address me by.

When I moved away to Long Beach, California in 2019, I didn’t realize it would be a powerful place for me to connect back to my ancestral roots. Long Beach is the second largest population of Khmer folx besides the country of Cambodia. It was where I got a chance to start over and explore who I really was, where no one knew me. Now, being back home in Seattle, I’ve reintroduced myself as Dany. It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness. It’s often pronounced wrong, which is an opportunity for me to step into my voice to correct others with the right pronunciation. This experience leads me to asking others of their name pronunciation frequently until I get it right to give respect and reverence to where these names originate from.

More Community Stories

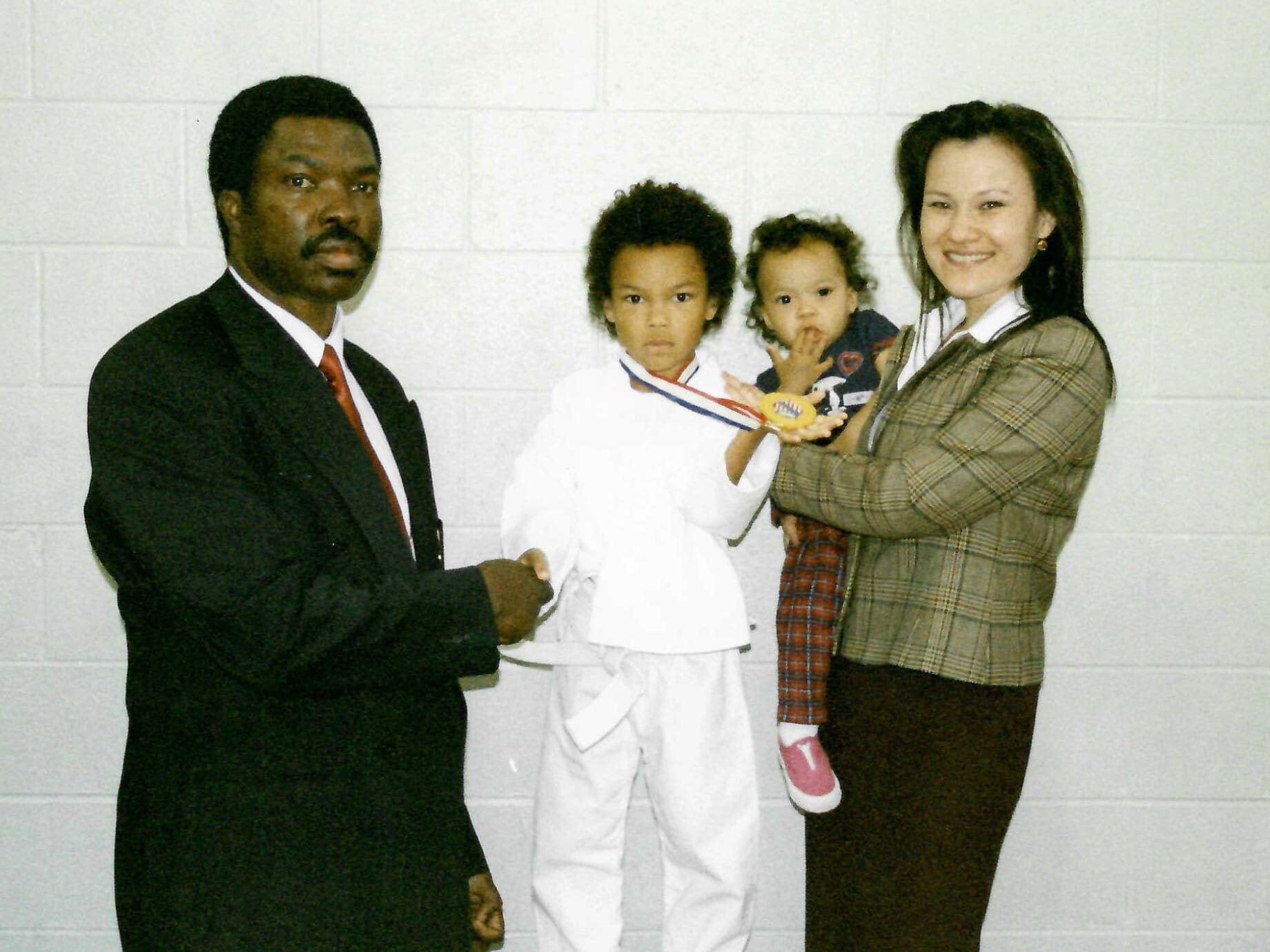

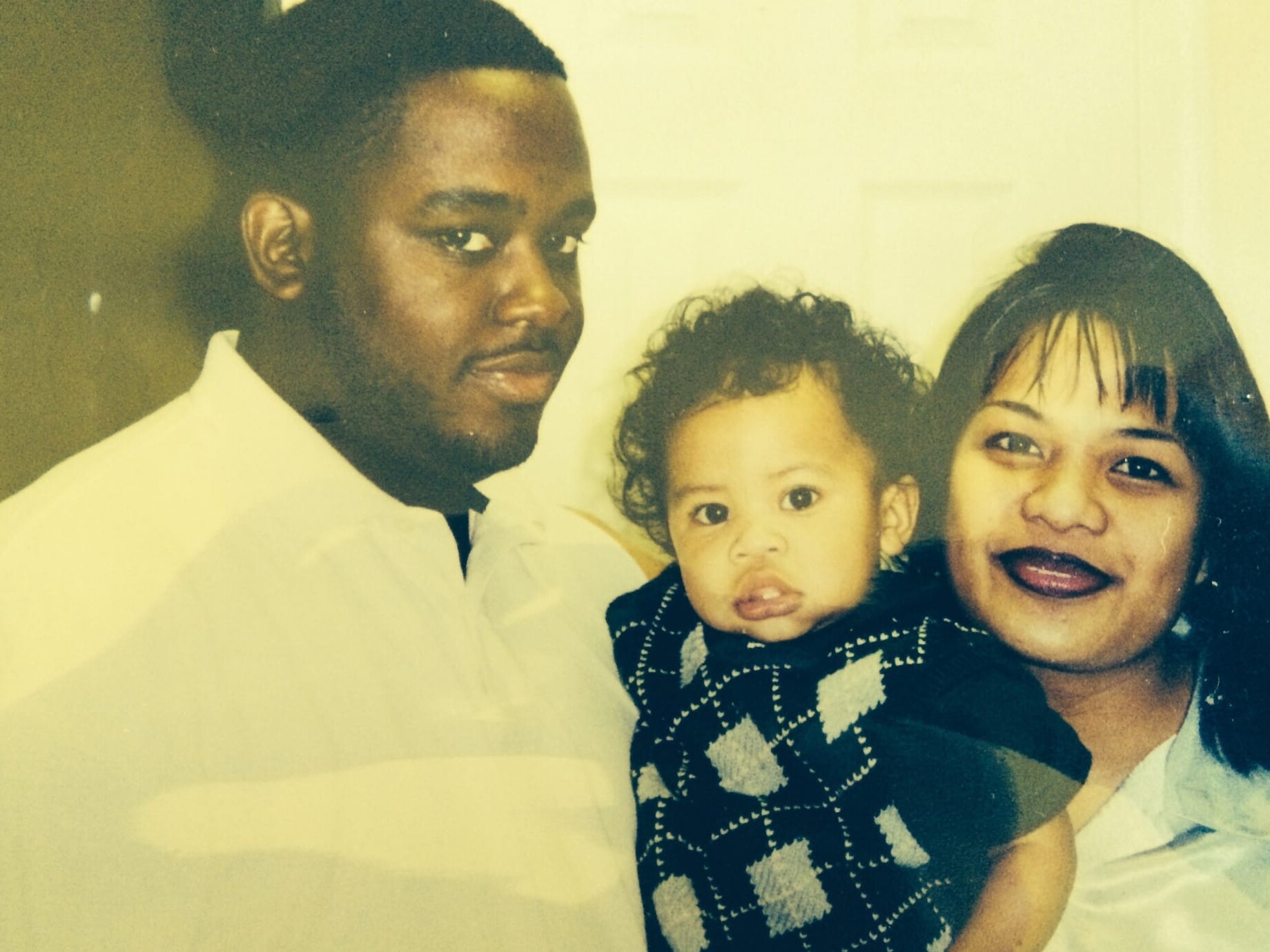

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

Jane Wong

"She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded...I keep forgetting my Chinese name."

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

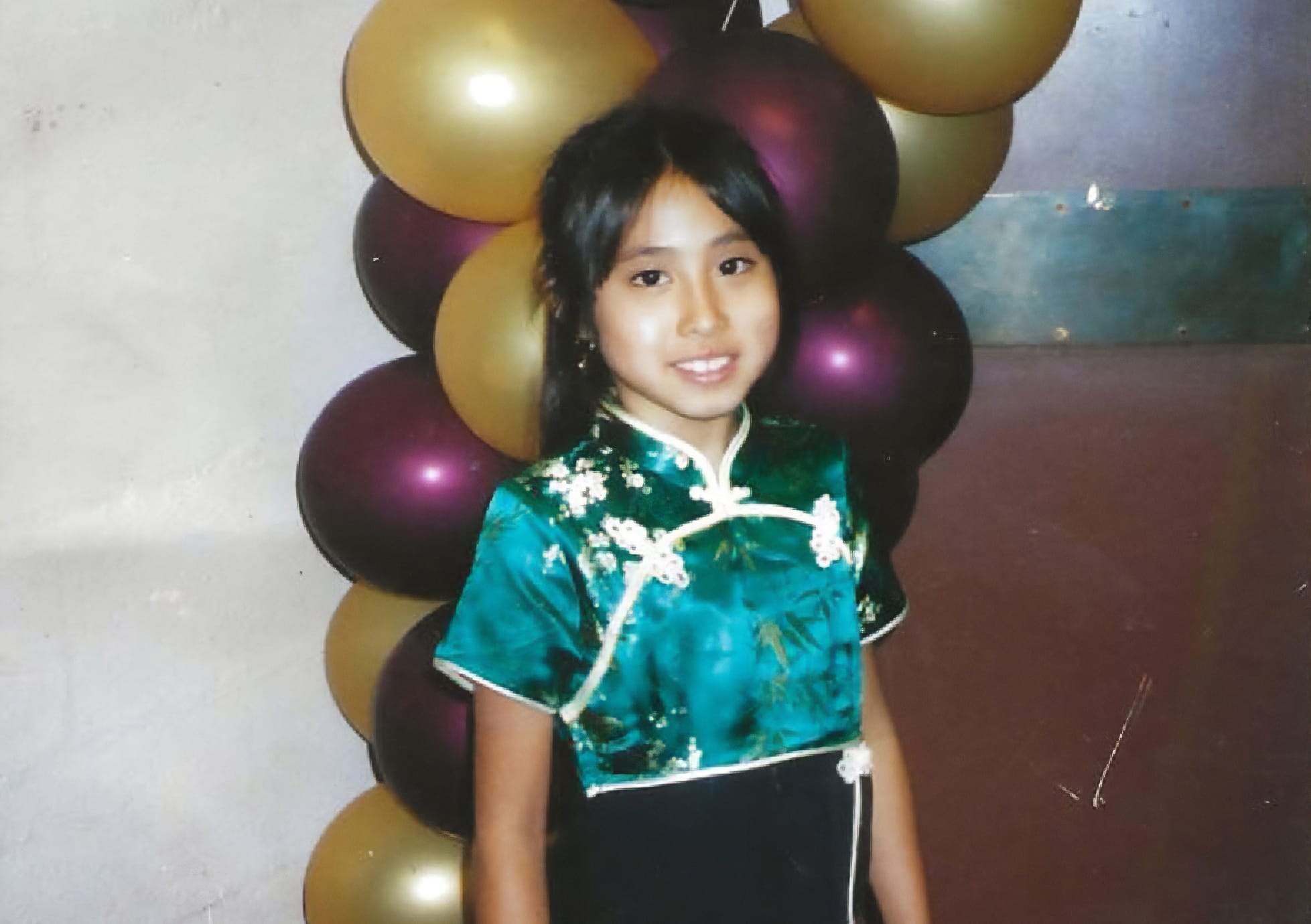

Jasmine Vu

Jasmine Vu

Growing up, I went to a predominately white K-8 Catholic school. Though I never had to experience the struggle of my peers not knowing how to pronounce my name, the topic of names was quite popular in those years. This made me more curious about my name and about my parents’ names because when they both got to America after the war, they chose American names for themselves. I asked them why and they just chalked it up to, “So it was easier for us to get jobs. That is why we gave you and your sister American names so you would not have to change your names in the future.” As a child who was already struggling to fit in, this sounded reasonable. It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival? Would I be more in touch with my heritage if I was given a Vietnamese name? Why did I have to grow up in shame surrounding my culture? Was my name meant to serve as a shield against this shame? I grew up loving my name and after reflecting on the context, I am still fond of it. It still has many ties to Vietnamese culture as it is a rice that is commonly eaten in the cuisine, a tea, and a native flower. My parents probably did not think this far when naming me Jasmine, but I think that the name encompasses my identity pretty well.

More Community Stories

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Jane Wong

"She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded...I keep forgetting my Chinese name."

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

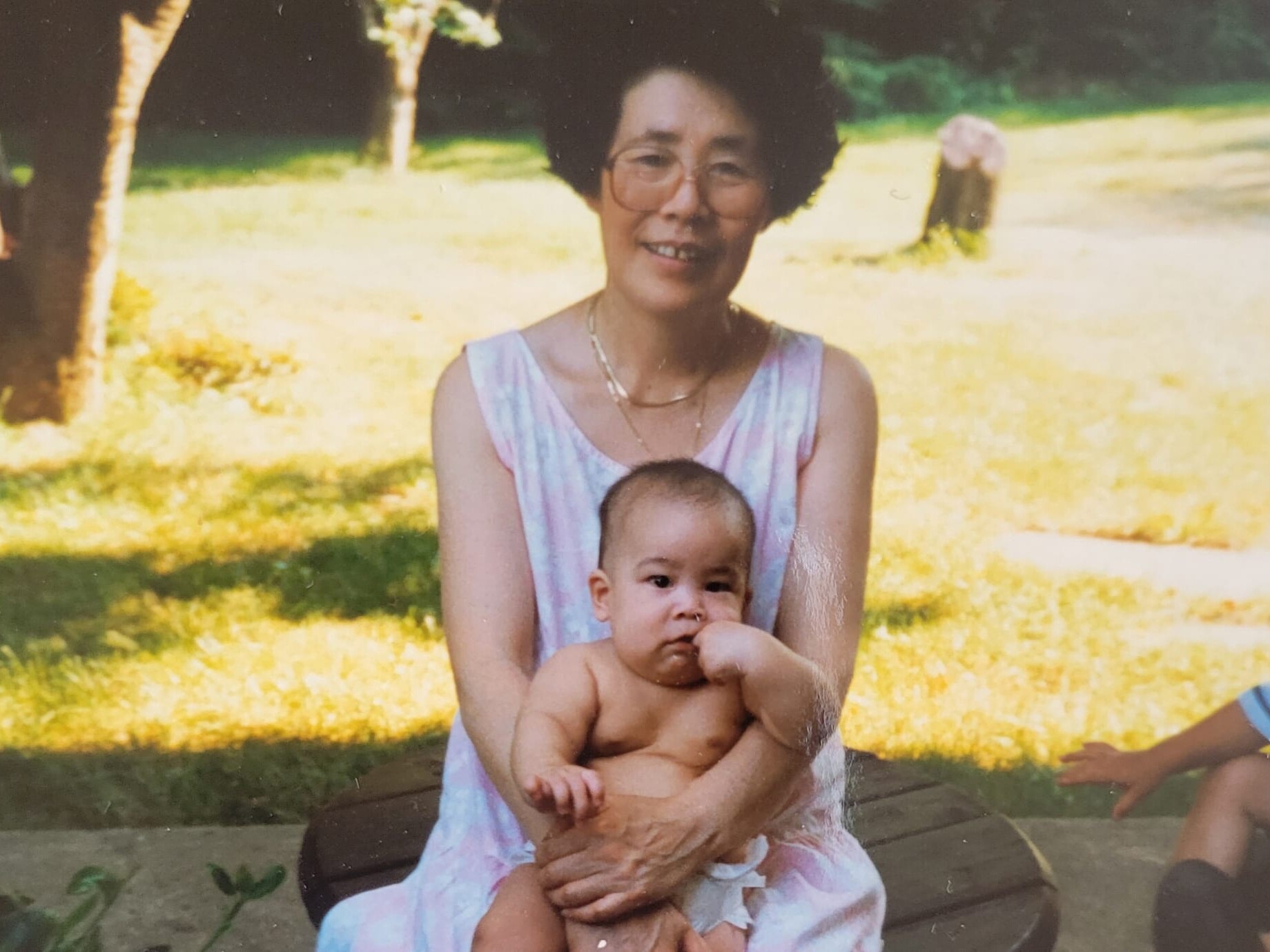

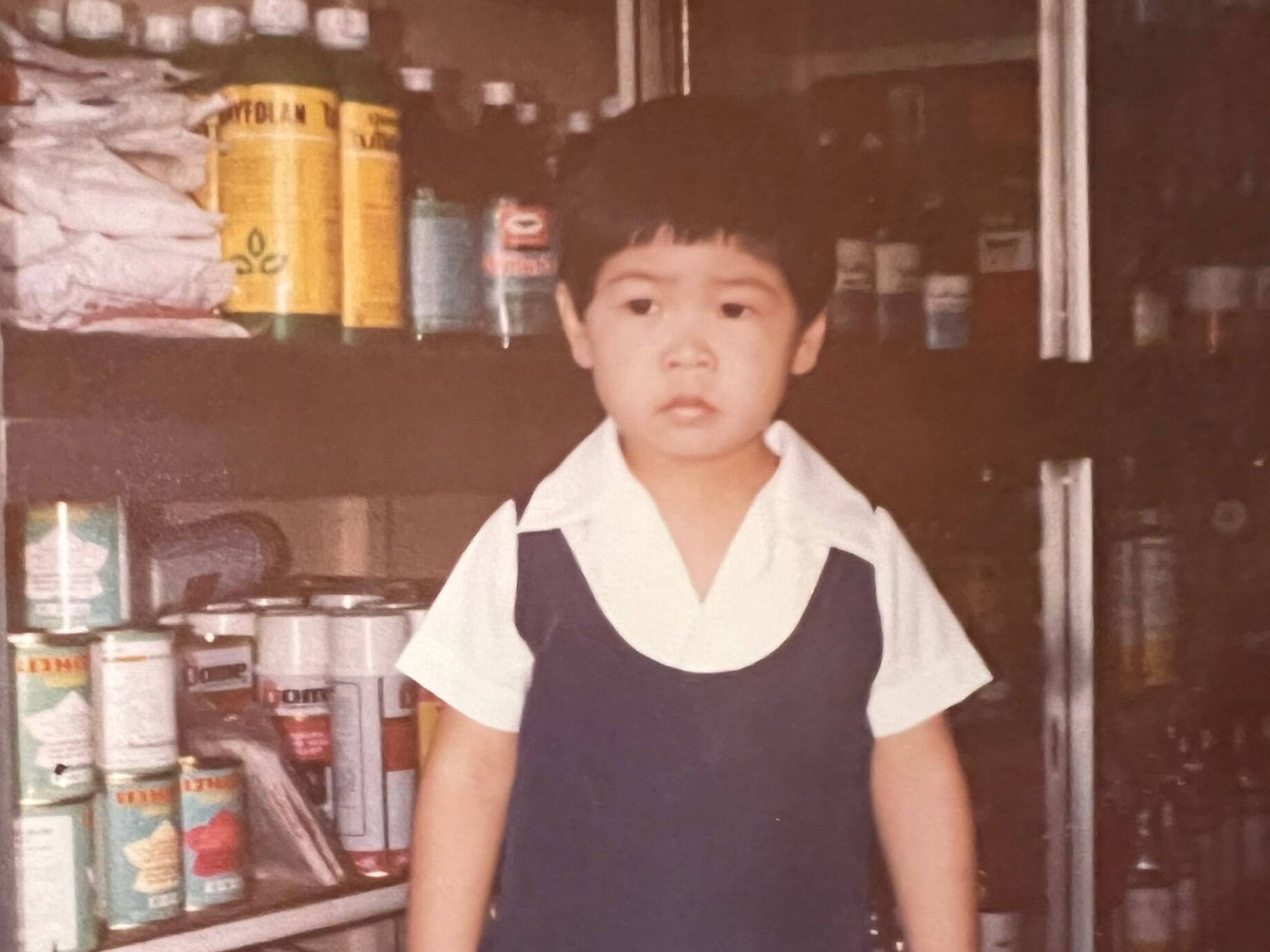

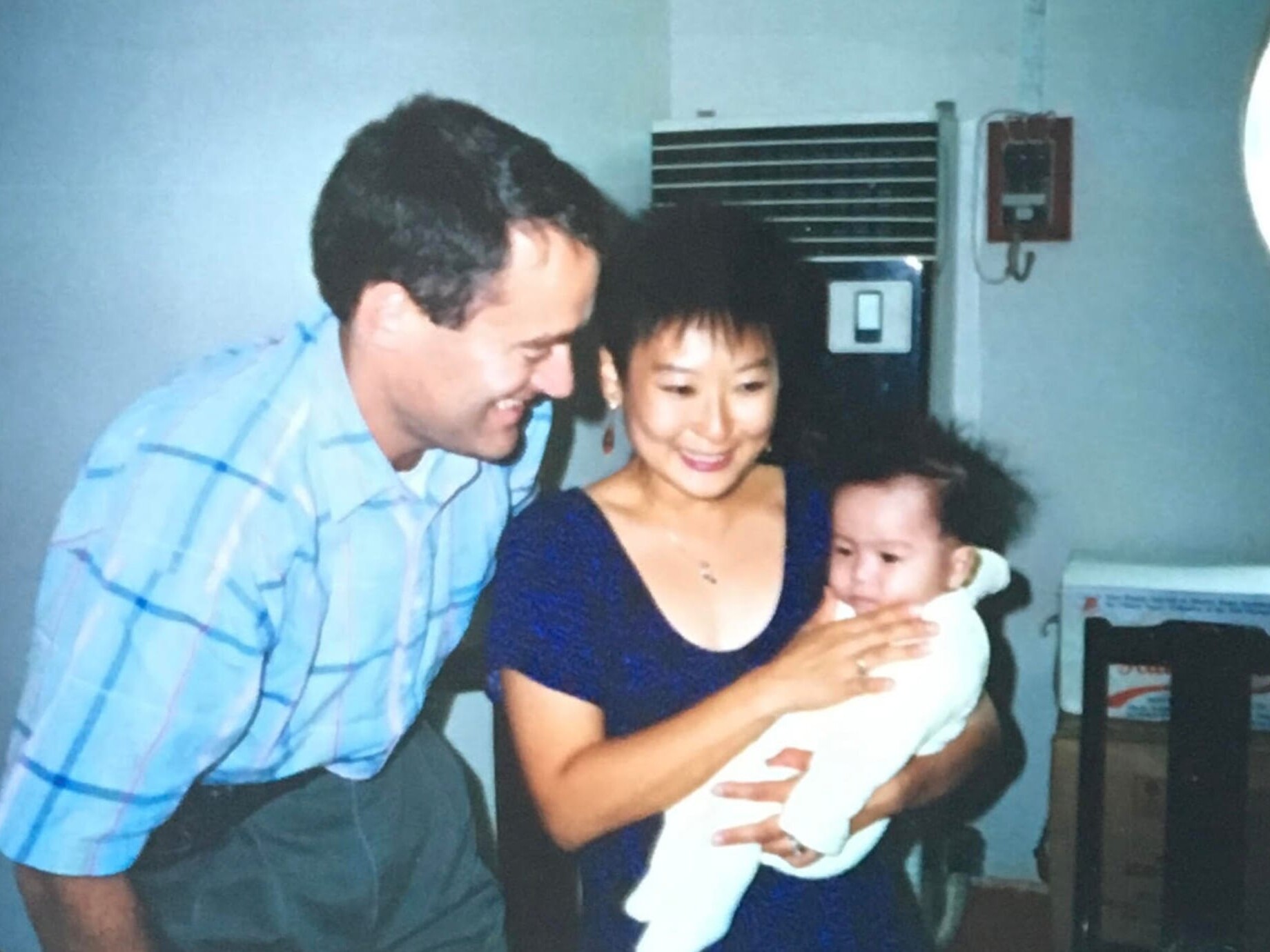

Carole Hsiao

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳

This is a picture of my family. I’m the youngest, less than a year old, wearing a checked jumper propped up by my mother. All of the adults in the photo are refugees from China, my father’s family, whose last name is Hsiao. My middle Chinese name, Hsi (which Microsoft likes to autocorrect), comes from a lineage poem that Hsiao relations from my generation share. My grandfather, who was a scholar at the University of Washington gave me my personal Chinese name “Lin” upon meeting me. It means gem and is written in a poetic manner. My aunts, who are in the back row, were the first females of our lineage to receive personal names. The name Carole comes from my mother’s first American friend. All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten. I grew up with expectations imbued by this family who transported their values from pre-1949 China. But I also grew up in America, where people who look like me are often silenced. I care about the rich history of my name but feel that my relationship to my history is changing. This year, I turned 60. It is said that I have completed a life cycle. This year I am also reclaiming my name and my identity, one that has often been erased by systems of power, to begin a new cycle that has yet to be explored.

More Community Stories

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

Jane Wong

"She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded...I keep forgetting my Chinese name."

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

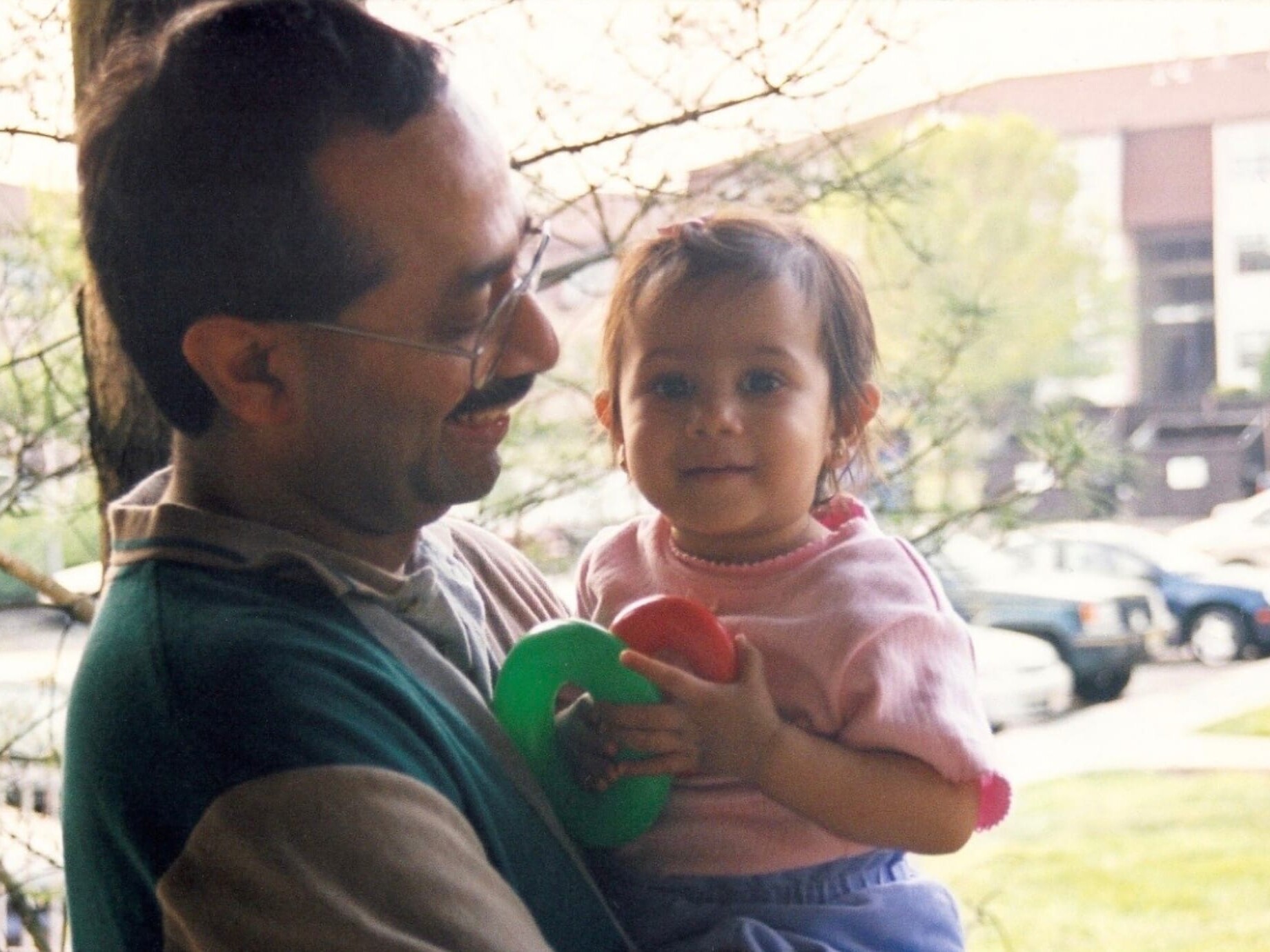

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

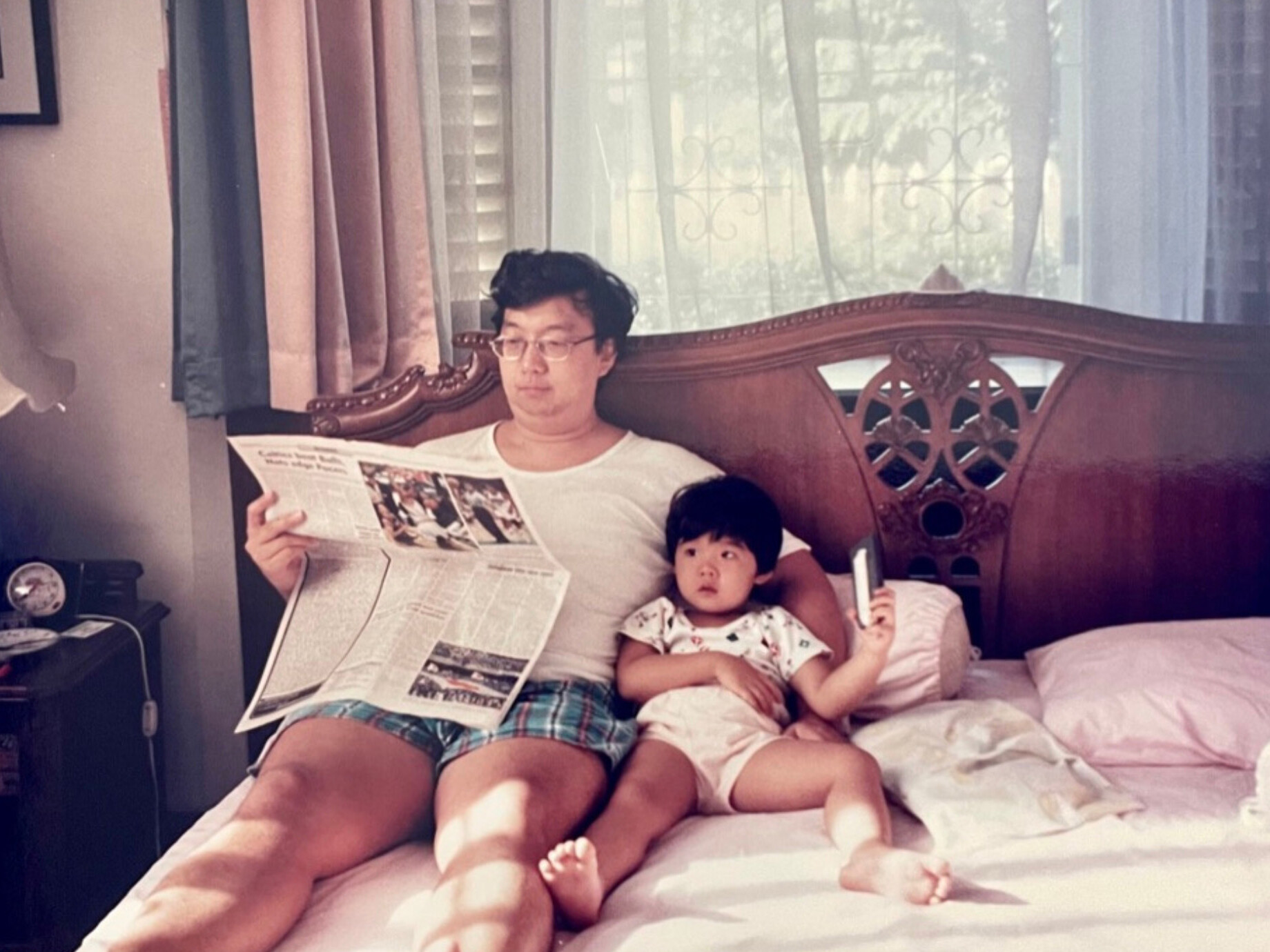

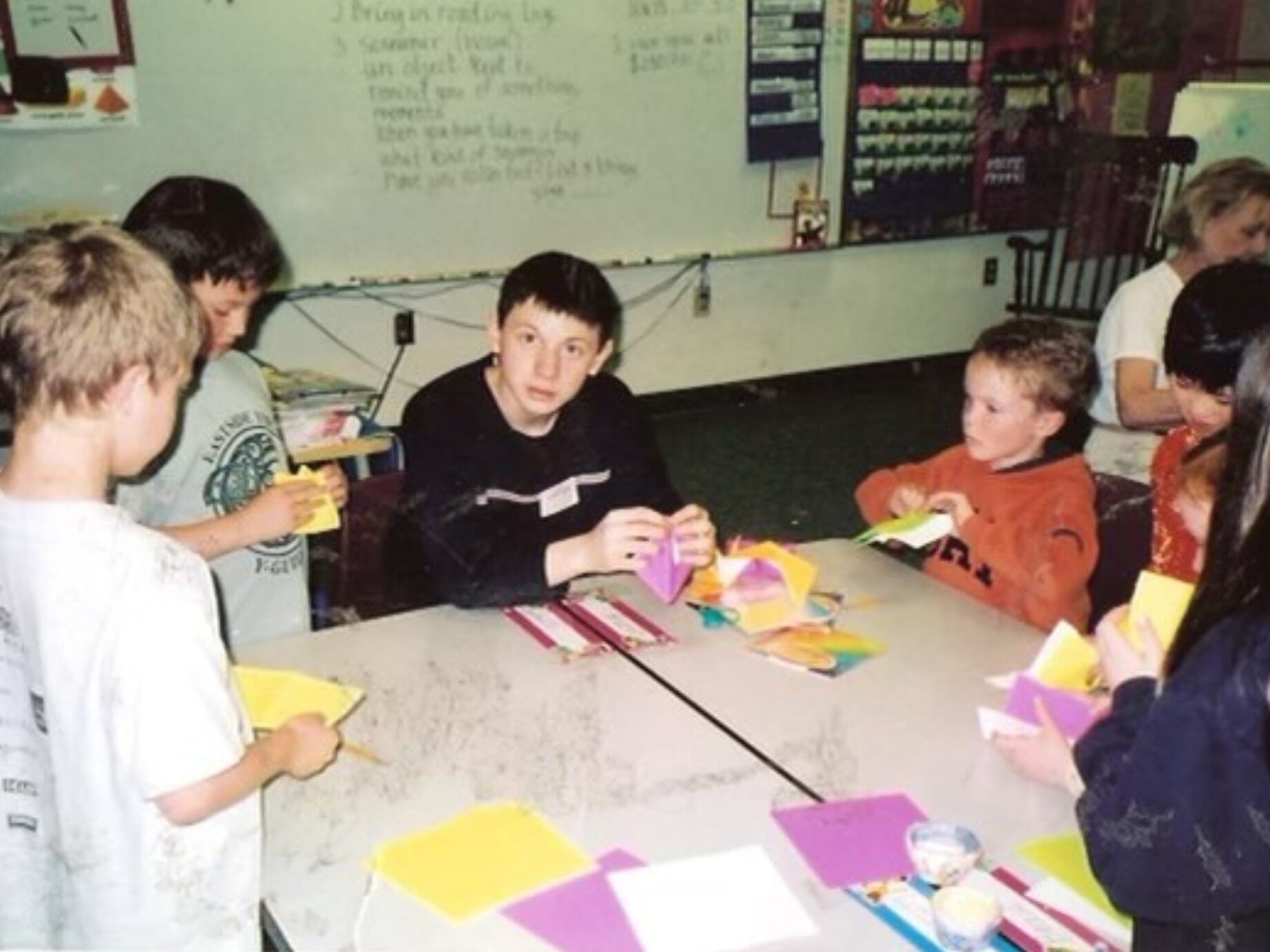

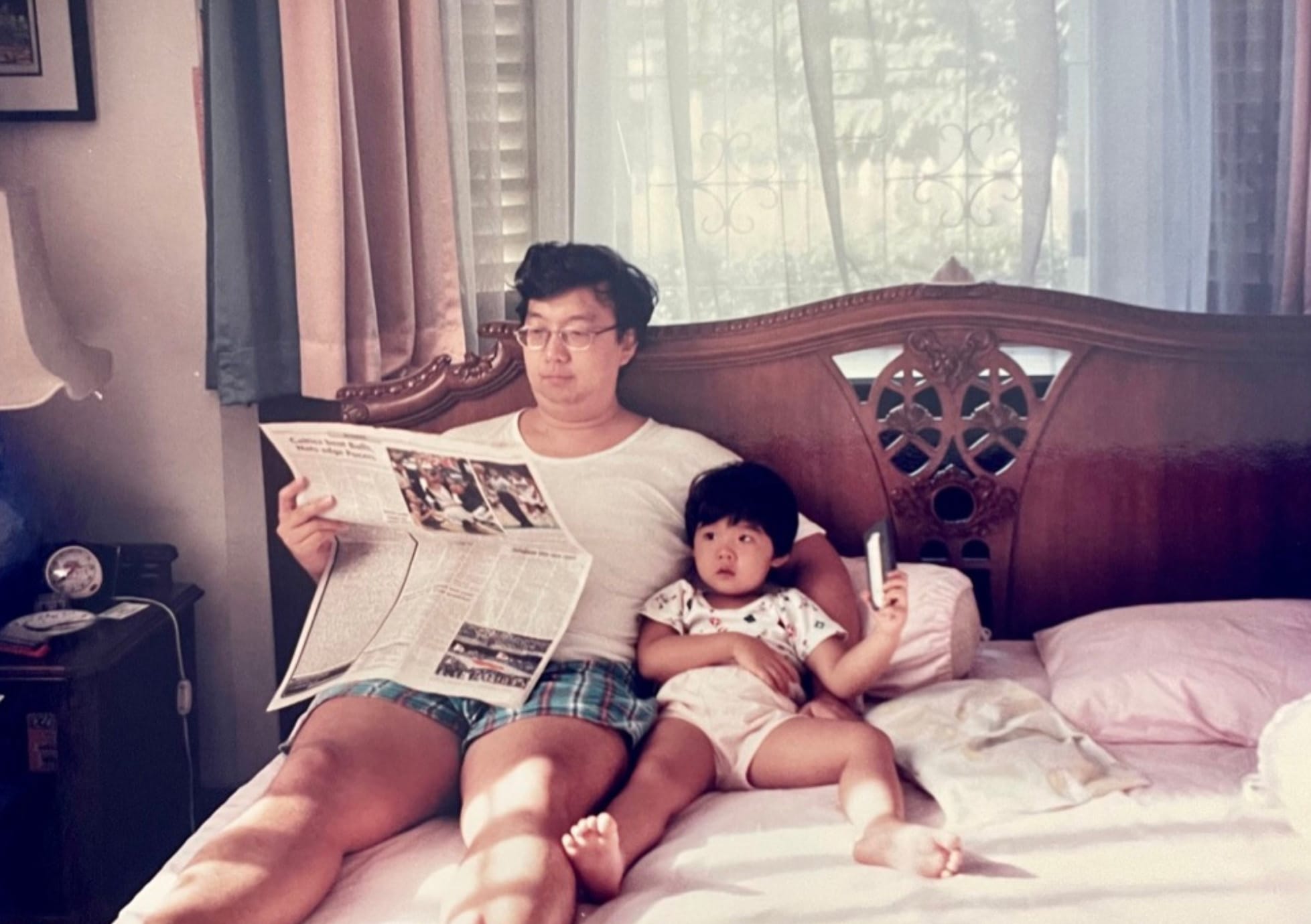

Evan Captain

Evan 田辺 Captain

My grandfather, an American, joined the military and met my grandmother in Yokohama in the 50s. My grandparents moved to the US and gave all their kids English names. Much of the rest of the story is defined by assimilation. I would hear my grandfather and grandmother speaking Japanese to each other, but it always seemed private. Last year, my grandmother taught us how to write 田辺, which is her mother’s family name from Hokkaido. In first grade, I told kids at school I was Japanese and then they insisted over and over as indisputable fact, “you don’t look Asian,” to which I had no response because I hadn’t learned yet that “Asian” was anything other than a continent. Learning about race in this specific way made it unfortunately very easy to stop learning about myself. That habit of self-erasing became stronger into my teens, witnessing the emasculation of Asian men and the fetishization of Asian women all around me. I thought that shrinking myself, silencing my Asian heritage, and defaulting to white masculinity preserved my normalcy. I have recently been feeling a turn towards mending and celebrating my lived experience as a Japanese-American. Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community.

More Community Stories

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

Eric Chan

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유

My three names are Eric Chan, 陳志宇, and 진지유. My legal name and first language is American English. My surname, generation name, and given name are Hong Kong Cantonese from our Yeh-Yeh 爺爺 (paternal grandfather), and my Korean name is a 漢字 – 한글 transliteration from our oe-harabeoji 외할아버지 (maternal grandfather).

As a child, I struggled to reconcile the regional dialects I heard at home with the standard, mainland languages I reluctantly studied in textbooks and classrooms on weekends in churches. I try to practice speaking more of both as an adult, but have never gotten comfortable or fluent enough in any version of Chinese or Korean. So my names are mostly written (族譜) and rarely spoken among friends and family. But this is already true in Asian communities. We often rather refer to one another not by name, but by relationship or seniority (哥弟姐妹, 오빠, 형, 누나, 언니, 막내).

I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent.

More Community Stories

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

Jane Wong

"She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded...I keep forgetting my Chinese name."

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

Renata Lumanau

Renata Lumanau

I am a Chinese-Indonesian woman. My name story revolves around my surname, Lumanau, from my dad’s side of the family. Our Hokkien last name Lauw was changed to “Lumanau” during Soeharto’s anti-Chinese rhetoric in 1963-1964. All Chinese-Indonesians were required to change our names to sound more Indonesian. When my dad was born, my great grandfather claimed the goddess Kuan Yin whispered to him that the baby boy should be called Lauw Tjhoe Kiam. Unfortunately, it wasn’t until he was around 5 years old that he had his name changed to Boedian Lumanau. His father felt a lot of grief changing his name to Bud Lumanau. However, it wasn’t until adulthood that my dad fully processed his loss of identity. His attempt to connect with his Chinese heritage was to learn Mandarin, which I remember him doing when I was 4 years old. I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one. During a lifetime of assimilation, my parents have adopted a ”we are world citizens” mindset, while I was always drawn to family stories that made me feel closer to my roots. I was hesitant to delve into this history since I’ve had a tumultuous relationship with dad but doing so helped me and my dad rebuild a relationship towards each other.

More Community Stories

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Cassie Whitebread

Cassie Whitebread

With a last name like Whitebread, I’ve always struggled with my sense of identity. I’m mixed-race; my mother is 1st generation Chinese, and my father is mostly Irish and German. The story goes that when my German ancestors immigrated through Ellis Island, “Weissbrot” was changed to “Whitebread.” I often reflect on how the insidious nature of assimilation impacted my mother as she navigated a very white town in New Jersey and chose to take on my father’s last name. For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. “Whitebread? But you’re not white.” I’ve heard every single joke and question about my last name that you can imagine. I fluctuate between despise for my last name and willing a sense of pride to protect myself from any impending ridicule or questioning from strangers. During those negative bouts, a fondness for this name that connects me to the men in my family pulls me out of the dark. This ongoing rollercoaster ride with my last name is inevitably tied to the sense of limbo that many mixed-race and biracial people feel―”Am I enough?” While growing up, I was hopeful of marrying someone to escape “Whitebread,” but I’m going to marry my wonderful fiance, whose last name is Groce (pronounced Gross). Whether or not I’ll take his last name is still up in the air.

More Community Stories

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Jane Wong

"She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded...I keep forgetting my Chinese name."

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Jane Wong

Jane Wong

My mom named me Jane at the restaurant where I grew up on the Jersey shore. My mother, very pregnant with me, was working the cash register at the restaurant when it dawned on her that she had to give her daughter an English name. To fit in.* She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded. The customer actually tried Maria first, but my mom couldn’t say it. Jane feels like it fits me―there’s something kind of old fashioned about this name. I keep forgetting my Chinese name, which literally translates to fragrant vegetable. Maybe it means nostalgia? It feels so embarrassing sometimes to forget how to say my Chinese name, to get the Toisanese tones wrong. Every single time I try to say it, it slips away from me like an eel.

Recently, I recorded the audiobook for my memoir, Meet Me Tonight in Atlantic City, where I say my Chinese name…and I forgot it again. I had to call my mom at work and ask her how to pronounce it. I dream of being fluent in my heritage language, dream of getting the tones right. If I can’t say my Chinese name, am I even myself?

*From Jane’s memoir, Meet Me in Atlantic City.

More Community Stories

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

Jane Wong

"She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded...I keep forgetting my Chinese name."

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Shin Yu Pai

Shin Yu Pai

My parents gave me the birth name of “Doris” June Pai, but I also received a Chinese name from my 3rd uncle a few weeks after I was born. He gave me the name “Shin Yu” which translates roughly as “happy treasure” or “optimistic jewel.” I went by the name Shin Yu until I went to kindergarten, when my name marked me as being different and was too difficult to pronounce for other kids and teachers. So I switched to Doris and used that name throughout my college years. My father has always associated the name “Doris” with his favorite celebrity, Doris Day, an actress that he associates with being American, innocent, multi-talented, and virginal. In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23. It’s not an easy name. People call me “Shin,” “Shin You,” or “Yu Pai.” I believe that names carry a dharma to them. I also have a Buddhist name―Sangye Drolma. It means Liberatress of the Buddha. In this way, I also view my Chinese name as having its own energy. I am fundamentally a more pessimistic kind of person so I think of my Chinese name, which was divined by my 3rd uncle to consider the elements and energies present on the day that I was born, functions like a dharma name―summoning and inviting forth the best parts of me.

More Community Stories

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

DeShawn Rivers*

"Growing up in Florida, I attended primarily black schools and classmates would often make jokes about my middle name by saying, 'That’s where the black is.'"

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Jane Wong

"She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded...I keep forgetting my Chinese name."

Jay Stoneking

Jay Stoneking

“Passing” is a double-edged sword of privilege. It’s a special kind of isolation that is hard to navigate. I am mixed and grew up most with my immigrant Vietnamese family. It was easy to catch my mom and aunts and uncles gossiping when I’d hear my name stand out awkwardly in a sea of Vietnamese from the kitchen. Growing up, it didn’t matter whether I spoke the language or that I didn’t look like any of them. It was enough to exist with them to feel at home in Vietnamese spaces. But away from them, I am invisible. I have always had an American first name and an American last name, completely disconnected from my closest family. I look mixed to me, but hardly ever mixed looking enough to others to be seen as Vietnamese or even Asian at all. Often people would say, “I didn’t realize you were Asian” or they’ll fish for my ethnicity when I mention being mixed or Asian American. It always hurts, even when I laugh it off; usually the person is Asian too. When I changed my name as an adult, I wanted to fold my heritage into my new name in some way but couldn’t bring myself to do it. It felt dishonest, as if I was appropriating from my own culture. Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do.

More Community Stories

Cassie Whitebread*

"For me and my mother, this last name adds an extra sticky layer of tension to meeting people for the first time. 'Whitebread? But you’re not white.'"

Taslim Jaiyeola Adejare Dosunmu*

"A part of me wishes my name expressed more of my mixed heritage, though my sentiments about that have changed a lot over time depending on the social context I was in."

Eric Chan 陳志宇 진지유*

"I must also remind myself that the folk arts I practice are traditionally performed and passed down anonymously, so we need not hold any of our names as sacred, precious, or permanent."

LiLi Marjorie Pigott

"I was born somewhere in China to a family that left me at a police station in Guangdong Province with no name or even a note with my birthday."

Evan 田辺 Captain*

"Much of my childhood and adolescence was shadowed by learning to hide that part of myself because that was easier than just existing in my own truth in a white community."

Jane Wong

"She asked a random customer to name me my “American” name and loved how simple it sounded...I keep forgetting my Chinese name."

Bonita Lee*

"It is fitting how this is the place of rebellion in China, as I was always rebelling against my own culture while trying to fit in when growing up in the United States."

Ashna Mediratta

"They had moved to the U.S. and were searching for a name that would be easy to pronounce with English letters and sounds, and would not be butchered by an American accent."

Sandy Ha

"I was given one name by my parents when we lived on a different continent. After living in this one for a few years, I chose a completely different name for myself. I was six. "

Jay Stoneking*

"Some days I wish I had, just to be more visible among my own community. Other days I feel grateful I don’t have to navigate racism the same way the rest of my family do."

Jasmine Vu*

"It was not until high school that I became increasingly aware of my identity as an Asian American, which turned into resentment. Why did my parents have to sacrifice their names for survival?"

Ren Han

"As my gender identity began to differ and change, I gravitated towards my online handle 'Ren.' It was more gender neutral, an ambiguous in-between to all the different iterations of my name."

Shin Yu Pai*

"In my early 20s, I traveled to Taiwan on a root-searching tour and upon coming back to the States, decided to reclaim my Taiwanese name, which I have used full-time since being 23."

Carole Hsi Lin Hsiao 蕭席琳*

"All of these names are written in distinct ways to convey political, poetic, and sentimental meanings and all of them are often misspelled or miswritten."

Jenn Ngeth*

"I remember the first time I heard my mother say my last name out loud. It was the first day of Headstart and just as easily as it slipped out of my mother’s mouth, it was too slippery for my teacher to pronounce."

Renata Lumanau

"I was able to learn Mandarin from a young age, but since we lived outside Indonesia since I was 3 years old, I felt disconnected not only from my Indonesian culture, but even more so from my Chinese one."

Linda Takano

"While Shay was easy to spell, this name would have its own challenges since it was also a common Irish surname. I could tell people were expecting a person who did not look like me. "

Dany Srey-Snow

"It’s an invitation for people to really know the authentic me, just like my family. I share how it’s a reclamation practice and it’s been welcomed with openness."